Some members of the Turkish minority in Bulgaria hope to raise awareness around the world of the human rights violations of the country’s authoritarian rulers against Turks in the 1980s.

On January 12, 1985, Ahmet Alpay, a 23-year-old student at the Technical University in Sofia, was arrested by the notorious Bulgarian secret police in a state under communist rule that was part of the Iron Curtain during the Cold War.

“It was a cold and snowy day when they forcibly entered our house, as if they were attacking a terrorist cell,” Alpay recalls of the police attack at the time. “They told my wife that I would be detained for a brief interrogation,” he said.

But after they left home, one of the secret members said to him, “If you try to escape, I’ll shoot you.”

As a member of the Turkish minority in Bulgaria, Alpay was not charged for anything as he was held in various detention centers until September 25, 1985, including the notorious Belene concentration camp on the Danube.

As a politically active Turkish student, Alpay opposed Bulgaria’s harsh assimilation policy, which was directed against the country’s Turkish minority, forcing them to change their names to Bulgarian and forbidding religious customs such as holding Muslim funeral ceremonies.

“The secret police (known as State Security, the Bulgarian equivalent of the KGB of the Soviet Union) accused us of making speeches and attitudes that violate the dignity of the state,” says Alpay, who is in the hands of the former Bulgarian authorities and pays a brutal price for the struggle to preserve one’s identity and dignity.

“I was punished for defending my natural human rights,” Alpay told TRT World on December 10th, celebrated worldwide as Human Rights Day.

“On the occasion of World Human Rights Day, I wish everyone whose rights have been violated in the world to regain them,” he says.

Ahmet Alpay is in the center of the picture next to his friends from the Belene camp after a meeting of their human rights organization BAHAD. (Photo credit: Ahmet Alpay / TRTWorld)

Under the autocratic leadership of Todor Zhivkov, Bulgaria’s communist state called its assimilation policy a “process of rebirth” with the aim of building a new Bulgarian identity without Muslim and Turkish elements. “It is based on the idea that there were and are no Turks in Bulgaria and rejects the existence of Turks in the country,” says Alpay.

“We copied our old identity cards that showed we had Turkish and Muslim names to prove them.” [Bulgarian communist authorities] and others that we are indeed Turks and Muslims, ”says Alpay, fighting back tears.

Bulgaria’s Turkish and Muslim population officially made up one tenth of the total population in the 1980s and owes its existence to Ottoman rule, which ruled much of the Balkans, including Bulgaria, for five centuries. Alpay assumes that the Turkish population was at least twice as high as the official numbers.

“She [Bulgarian communist state leaders] believed that the Turkish population could at some point exceed the ethnic Bulgarians because the Turks had more children than they, ”says Alpay, explaining the political logic of the government’s assimilation policy at the time.

Like many other Turks in Bulgaria, Alpay was offended by Sofia’s policies of assimilation, organizing Turkish youth and calling on foreign embassies to tell them that the state had violated the human rights of its Muslim minority, which angered the autocratic leadership.

In 1989, Alpay and his family, including his one-year-old baby, were deported, forcing them to abandon their entire life and village in Kircaali, a Turkish-majority town near the Turkish border, as well as forcing hundreds of thousands of Turks to move to others in the same year Countries to emigrate.

The Bulgarian authorities also took away his engineering degree when he was deported. “When I asked them why they were doing this, they replied that they wanted to make sure I didn’t get a good job and that it was difficult to make a living,” says Alpay.

Ahmet Alpay, seated on the left, is pictured with his friends while they were studying in Sofia. (Photo credit: Ahmet Alpay / TRTWorld)

After he was abruptly sent by Bulgarian authorities to Stockholm on a so-called relatives visit (although they have no relatives in the Swedish city), Alpay eventually emigrated to Turkey.

No regret

After almost four decades, Alpay has no regrets.

“My friends and I did what we should have done back then in this political era,” said the now 60-year-old automotive engineer, who is currently retiring in Bursa, a city in the north-west that is heavily populated by Turkish migrants from Bulgaria.

“We just feel bad because all the people who have insulted and tortured us have not yet been punished,” he says.

While he regrets that the international community has not persecuted her like Serbia’s Slobodan Milosevic and others for her war crimes against Muslim Bosniaks, Alpay remains a politically active man who demands justice against these Bulgarian perpetrators.

Today, on the occasion of World Human Rights Day, he discussed his painful story during a meeting organized by the Swedish Raoul Wallenberg Institute for Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (RWI) and the Turkish Association for Justice, Rights, Culture and Solidarity in the Balkans (BAHAD ) was organized. .

“I spoke about the need to bring perpetrators of human rights violations from the communist era in Bulgaria to justice,” says Alpay, who is also part of BAHAD, a Bursa-based NGO that aims to expose human rights violations. to which Alpay and others were exposed.

Seek justice

Many Turkish victims like Alpay had high hopes for the formation of a democratic government after the collapse of communist rule in 1991. “But our expectations were in vain,” he says.

In 1991 the Bulgarian government opened an investigation to prosecute crimes against the Turkish minority. But after three decades no one has been charged or imprisoned for their crimes. “It was just a mock dish,” says Alpay.

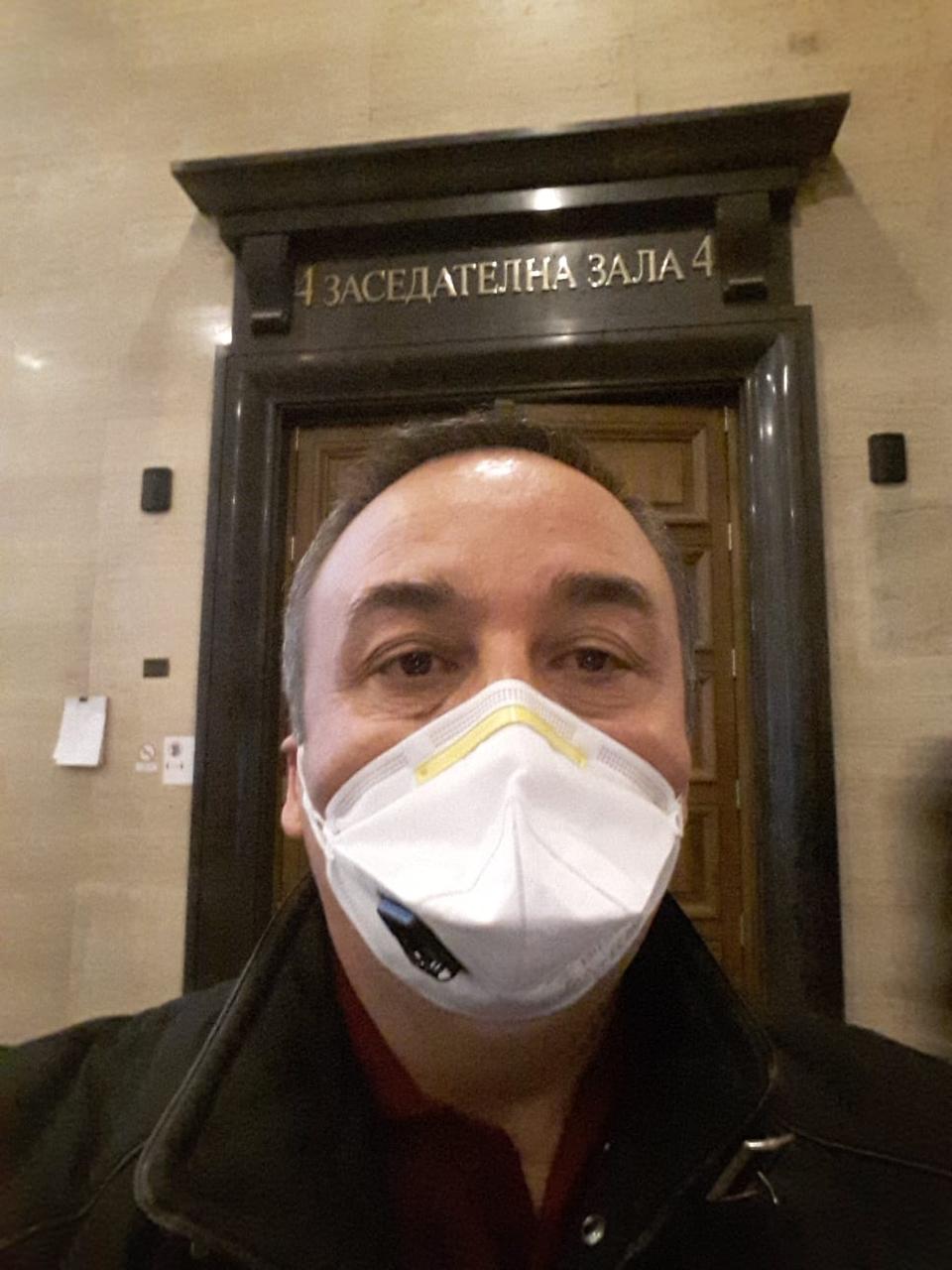

Ahmet Alpay stands before the Bulgarian court, where he is prosecuting his case on the human rights violations of the former communist regime (2021). (Photo credit: Ahmet Alpay / TRTWorld)

Safiye Yurdakul, the president of BAHAD, whose father was also imprisoned in Belene concentration camp, agrees with Alpay. “It has been on the indictment stage for 30 years. But we continue to fight for justice against these perpetrators and open various lawsuits against them, ”Yurdakul told TRT World.

As Bulgaria is unwilling to prosecute these violations in the past, BAHAD and other Turkish groups want to bring their cases to institutions such as the International Criminal Court (ICC) in order to achieve justice.

“In today’s meeting with the RWI we discussed this topic and asked them why the international community did not care about human rights violations in the communist era of Bulgaria,” says Yurdakul.

“Belene was Europe’s last concentration camp,” says Yurdakul, something that the EU and other European groups cannot ignore.

Belene warehouse

The most notorious human rights violations occurred, among other places, in the Belene camp, which, ironically, was located on a naturally beautiful Bulgarian island.

In early 1985, Alpay was first imprisoned in a state security prison. On March 25th he was sent to Belene. “The day we entered the concentration camp was a freezing cold day and a cold wind was blowing so strong. They took off all of our clothes on the very first day to insult us, ”says Alpay.

Ahmet Alpay shows where his bed is in his cell in the Belene concentration camp (2018). (Photo credit: Ahmet Alpay / TRTWorld)

A small cell held 20 prisoners and there were no toilets. “Because we had to use a sink for our toilet needs, the cell smelled terrible. We couldn’t breathe properly, ”he says.

“There were other cells where robbers, murderers and other common criminals lived. They have much better conditions than us. she [Bulgarian camp authorities] gave us junk food. They treated us like prisoners of war, ”he says.

The relatives of the Turkish prisoners did not receive any information about them either. “They spread rumors that our relatives were told that we were shot because we were trying to escape from prison in Romania using the frozen Danube as an escape route,” he recalls.

He met his relatives after 141 days, but was unable to speak to them in his mother tongue, Turkish, because of the state ban on the language. “My parents couldn’t speak Bulgarian because they were old people. Because of the ban, we just looked at each other to make sure we were okay, ”says Alpay as the tears continued to flow.

According to official Bulgarian information, there were 517 Turkish prisoners in Belene. But Yurdakul, whose father was also in Belene, believes the number was much higher.

Source: TRT World

https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/bulgaria-s-turks-persecuted-by-former-communist-regime-seek-justice-52526

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/JEUL2B5V7BJCFMRTKGOS3ZSN4Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/DYF5BFEE4JNPJLNCVUO65UKU6U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/UF7R3GWJGNMQBMFSDN7PJNRJ5Y.jpg)