Even without the iconic moment he will forever be famous for, Tommie Smith has a remarkable life story.

From son of a tenant to world-famous world-class athlete, outcast and respected speaker, his journey is a great American story.

Too much to be told in a column of this length.

Spend an hour with Smith as I recently did and you will be inspired and want more of a man whose admirable, life-changing sacrifice for principle, a “cry for justice,” as he describes it, proved so costly Has.

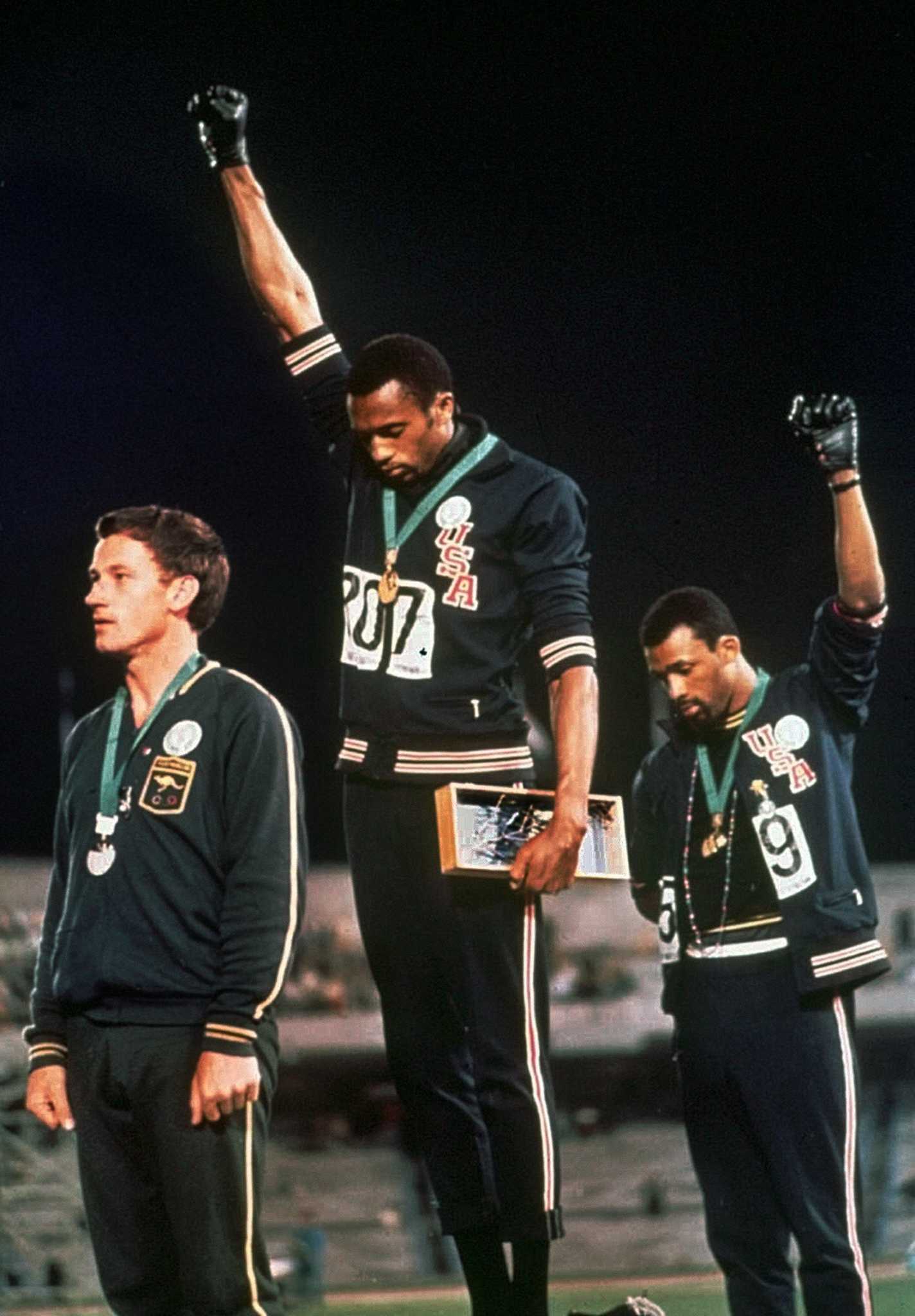

Smith may be celebrated now, but after his and teammate John Carlos’ Black Power salute on the podium at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, he was kicked off the Olympic team and said he had 24 hours to explore the country to leave.

He was not welcomed as an Olympic champion in the United States, but was despised for having the courage to challenge racism through a silent protest.

Death threats were abundant in the late 1960s and, shockingly, still trickle today long after the civil rights movement. He used to lock the hood of his car for fear of a bomb being placed in his car.

Remember, the gestures of Smith and Carlos came just six months after the nation was rocked by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

If you’re curious about how their actions were shared with the world, Smith and Carlos said that their closed fists after winning gold and bronze medals, respectively, are a symbol of black men coming together in America.

An Associated Press article described them using their “black shrouded” fists to deliver a “Nazi-style salute.”

“That act was not against the flag,” said Smith. “It wasn’t against the country. It was for that. Out of the hope that it will live up to its ideals. That was our prayer. Why our heads were down

“We were up there for a nation that did not offer all of its own people the same freedom that was not what their ancestors wrote.”

Smith was born in Texas to migrant workers. When his family moved to California, he also joined them in the cotton field in the evenings after school.

When he told his father that the headmaster of his elementary school suggested representing the school at an athletics meeting, his father gave him permission but told him he’d better win.

“If you lose, you and your brothers and sisters will pick cotton again.”

Smith, the seventh of 12 children, did not lose. And he ran on.

By high school, he was an all-round athlete and a superstar in three sports – soccer, basketball, and track and field. Especially in the latter, he shone with a long frame and an impressive step that was suitable for sprints.

“I was able to pick it up and put it down,” said Smith, who was the first man to run the 200 meters in 20 seconds.

When the 1968 Olympics were held, Smith was a world record holder and a gold medal favorite. He was also part of the Olympic Human Rights Project, a group of athletes who called for a change in Olympic policy with countries like South Africa.

When there wasn’t enough support for a large-scale boycott of the Games, athletes were told to do what they were comfortable with.

“That was a lot bigger than a guy in the winners’ stand with his fist up,” said Smith. “It was a movement. Our campaign simply got more attention back then. “

As you can imagine, Smith has a strong feeling for this generation of athletes who have become more open in recent years, bringing silent protests to the field and the courts.

“We have platforms and we now have young people who don’t hesitate to speak up,” said Smith. “In the days of Tommie Smith and John Carlos, we didn’t have a lot of action when black athletes were together.

“It was so gloomy at the time that people applauded going to a restaurant, ordering a hamburger and actually getting a hamburger. Fortunately, we are not dealing with the realities of the past, but there is still a lot to be done and athletes should continue to work towards equal justice.

“This is a race. This is a race for freedom. Athletes have every right to get up and they should get up. This is America. “

In the race of his life, despite a slow start from a hamstring injury, Smith set another world record with a 19.83-second run, a mark that stood for 16 years until Carl Lewis broke it at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

I asked Smith if he would be sent back in time, which he would do differently.

“I wouldn’t throw my hands up 20 meters from the finish,” he said with a smile. “I was in the running for victory and that was a cheering aspect of winning. The smile you saw on this young 24 year old Tommie Smith’s face as he crossed the finish line was a real smile. But after the race I said, ‘Man, why did I do this?’ “

Smith said the older he was, he would tell the younger self to stop the race.

“Don’t eat your food before it’s served,” he said.

Otherwise, Smith prides itself on his place in history. And for a good reason.

jerome.solomon@chron.com

twitter.com/jeromesolomon

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/JEUL2B5V7BJCFMRTKGOS3ZSN4Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/DYF5BFEE4JNPJLNCVUO65UKU6U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/UF7R3GWJGNMQBMFSDN7PJNRJ5Y.jpg)